On Sale Jan 6, 2004 A Delacorte Book

On Sale in the UK

On Sale in Germany May 2003

|

|

|

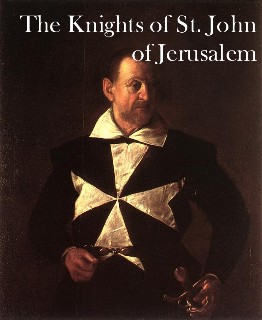

The Order of St. John of Jerusalem, known as the Hospitaller Knights of St. John, the Knights of Malta, and the Knights of Rhodes During

the First Crusade, Christian pilgrims making the journey to the Holy Land

were protected by two |

|

|

Driven from Jerusalem

by Saladin, the two Catholic orders of professed monks moved to Acre, the

last capital

Though their numbers

were small, the knights were tough men to whom pillage came as easily as

prayer. Their ranks were filled with noblemen hailing from the greatest

houses of Europe, men who served their Grand Master under vows of poverty,

chastity, and obedience. The noble houses took great pride in the number of

knights on their family tree, pledging their sons to the Order at birth. The sun was just beginning to rise over the Ottoman Empire. Rhodes lay athwart the empireís shipping routes, and the increasingly militaristic knights interrupted trade between Istanbul, the Levant, and Egypt. Muslims making their pilgrimage to Mecca were captured and enslaved. For many years the knights gnawed thus at the Ottoman bellyónever strong enough to present a military threat to the empire, but ever an irritation. Determined to drive out the infidel, Mehmet, the sultan who conquered Constantinople, mounted a fierce siege of Rhodes. The Order had heavily fortified the island, and Mehmet was unsuccessful. Suleiman drives the Knights from Rhodes. Such was not the case with Mehmetís son, Suleiman. In the first major military campaign of his reign, he took the city of Belgrade, striking at the door to central Europe. The next year, only his third as Sultan, he turned his attention to Rhodes. The knights fought bravely but stood no chance against the four hundred ships and five army corps of Suleiman. In victory, the Sultan showed magnanimity toward his enemies out of respect for their valor. He allowed the knights to leave Rhodes with their banners and their honor, their arms and their relics, their camp followers and even their animals, in exchange for their solemn oath that they would leave his minions in peace. It was an oath the knights would not keep. Malta.

For seven years the Order had no home,

taking only transitory residence in Sicily and Italy. In 1530 the knights

were It is hard to imagine who was more unhappy at the arrangement: the knights, dismayed over the barren, impoverished, and poorly-defended land; the nobles and peasants of Malta, resentful and suspicious of their new and foreign rulers, who did not bother even to learn their language; or the Ottomans and their allies the corsairs, who realized that the harbors of Malta were perfect for sheltering the troublesome knights, who now commanded the vital sea lanes between Sicily and North Africa.

In 1530 Grand Master L'Isle Adam was received

by Malta's unhappy nobles at Mdina, an ancient walled city which at the time

was the island's capital. The seafaring knights preferred to build their

convent in the fishing village of Birgu. They slowly began fortifying the

area around the Grand Harbor against the Ottoman attack After the Great Siege, a new and more heavily fortified capital was built on Sciberras, a peninsula overlooking the Grand Harbor. The city was called Valetta, after the Grand Master who led the island's defenders against the Ottoman attack. The knights continued their traditions of maintaining one of Europe's finest hospitals, of raiding enemy (Muslim) shipping, trading in slaves, and, of course, drinking and debauching. In 1798 they were driven from Malta by Napoleon. Once again they had no permanent home until 1834, when they established a new headquarters in Rome. In recent years the Order has been refurbishing Fort St. Angelo. Organization of the Order. The

sovereign Order of St John was created under protection of the Pope. It was

ruled by a Grand Master, elected for life by the knights. He presided

over the Sacro Consiglio, a governing council composed of the Orderís

highest officials. The Convent of the Order was scattered through

Birgu, an old fishing village that lay on the small peninsula behind Fort

St. Angelo, the Norman castle where the knights made their headquarters. The

convent consisted of the conventual chapel of St. Lawrence; the hospital, or

Holy Infirmary; the arsenal, where the Orderís galleys were maintained; and

the separate auberges, or dormitories, where the knights from each of

the Orderís eight langues, or nationalities, lived while at

convent. Those langues were of Auvergne, Provence, France, Aragon,

Castile, England, Germany, and Italy. Each langue was ruled by a

pilier, or master, Classes of Knights. There were three classes of knights. First among them were the knights of justice, those most pure of blood, whose shields bore no fewer than sixteen quarterings of hereditary nobility. Of second rank were conventual chaplains, ecclesiastical knights whose service was devoted to work in the hospital and chapel. The third rank were serving brothers, knights who were of respectable if not strictly noble birthóso long as they were not bastardsóand who served as soldiers. In addition, there were magistral knights and knights of grace, honoraries appointed by the Grand Master and confirmed by the council. Each knight was initiated in an elaborate ceremony of investiture, in which he swore oaths of poverty, chastity, obedience, and allegiance to the Grand Master. The novice would then serve three seasons, or caravans, as an officer in the galleys. Afterward he would either return to the convent, to his estate on the continent, or to one of the priories or commanderies maintained by the Order in each of the countries from which the knights hailed, the income from whose crops and holdings went to support the convent. A knightís first promotion would be to commander, at which time he would be paid a salary to help defray his costs. A knight could always supplement his income by investing in a private galley, so long as its profits were shared with the Orderís insatiable treasury. A knight might live in the convent or rarely visit, participating only in the General Chapters, the assemblies held every five years, or answering the emergency summons of the Grand Master. The warrior-monks of Jerusalem grew much more worldly as the knights of Rhodes and then Malta, their pursuits sometimes more visceral than spiritual. In theory, the convent was a united stronghold of knights, resolute in their faith and dedicated to a common purpose. In practice, the convent was an unruly nest of strong-willed nobles of eight nations, men united by vows but often divided in politics, their families prominent participants in the religious and political conflicts sweeping the continent. The Cross.

Click for a link to a detailed history of the Order's cross. Click here for link to a General History of the Order Click here to visit the official site of the Order of St. John |

|

granted

the small and barren islands of the Maltese archipelago, along with the city

of Tripoli on the North African coast, by the Hapsburg Charles V, the

Holy Roman Emperor and king of Spain. Charles knew the wisdom in having such

a military force to protect his southern flanks from Suleiman and his

allies, the corsairs of the Barbary Coast. Charles set rent for the island

at the annual payment of a falcon.

granted

the small and barren islands of the Maltese archipelago, along with the city

of Tripoli on the North African coast, by the Hapsburg Charles V, the

Holy Roman Emperor and king of Spain. Charles knew the wisdom in having such

a military force to protect his southern flanks from Suleiman and his

allies, the corsairs of the Barbary Coast. Charles set rent for the island

at the annual payment of a falcon. that all knew was inevitable.

that all knew was inevitable.

At

the time of the Great Siege the knights wore two crosses. One, borne

on pennons and tunics, was a squared white cross

At

the time of the Great Siege the knights wore two crosses. One, borne

on pennons and tunics, was a squared white cross